Despite stable economic growth, the decrease of the shadow economy in Latvia has been minimal - 0.3 percent

According to the results of the latest study, the shadow economy in Latvia has slightly decreased.

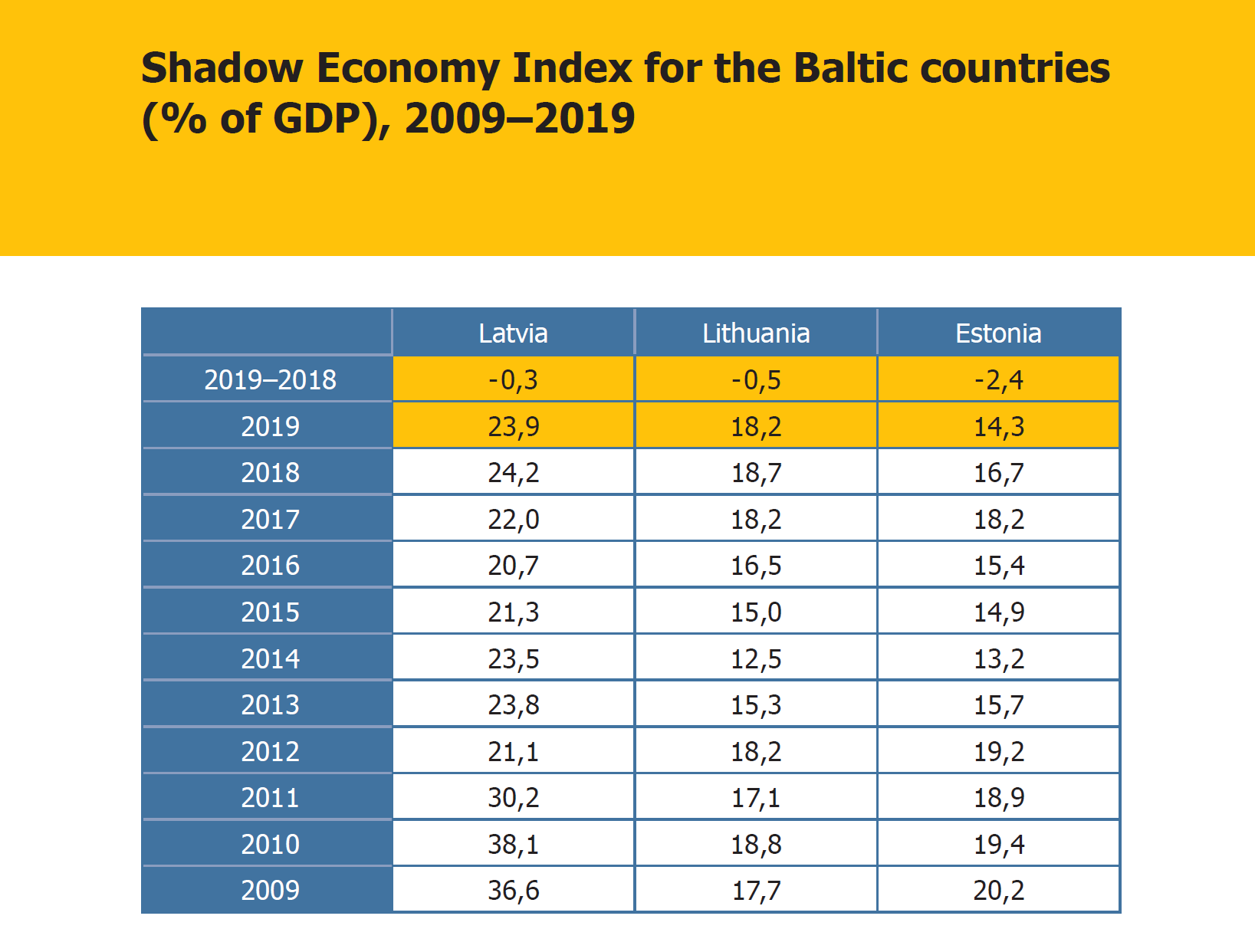

The results of the “Shadow Economy Index for the Baltic Countries”, presented today by the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga (SSE Riga), show that in 2019 the shadow economy in Latvia has slightly decreased - by 0.3%, now reaching 23.9% of the national GDP.

In 2019, the size of shadow economy also decreased in the neighbouring countries - in Lithuania by 0.5% and in Estonia by 2.4%, reaching 22.0% and 18.2% of the respective national GDPs.

The author of the Index, professor at SSE Riga Dr. Arnis Sauka, acknowledges: “It is believed that as the economic situation improves, the shadow economy should shrink, as entrepreneurs are doing better and are more motivated thus to pay taxes. However, this may not be the case if, for example, businesses do not trust that tax money will be used properly, if there have been corruption or other scandals that have damaged public confidence in government, or if appropriate support measures have not been taken to improve the business environment or to limit the shadow economy. Unfortunately, we can conclude that in the previous 3-4 years, as the economy of Latvia has grown, the size of the shadow economy, in general, has not been reduced. The economic downturn caused by COVID-19 is likely to increase the growth of the shadow economy in both 2020 and 2021.”

The most important component of the shadow economy in Latvia in 2019 is still “envelope” wages, which comprise 44.1% of the total shadow economy in Latvia.

The average share of wages (%) hidden by entrepreneurs from the state in 2019 is relatively similar in Lithuania and Estonia (11.5% and 14.1%, respectively), but is significantly higher in Latvia (22.3%). “Envelope” wages in Lithuania and Estonia in 2019, compared to in 2018, decreased (by 5.2% in Estonia and by 1.4% in Lithuania), while in Latvia there was an increase (by 0.8%). “According to the results of the study, there is an increasing gap between the level of envelope wages in Latvia as compared to that in other Baltic countries. Taking into account the expectable economic downturn in the coming years, action is urgently needed to deal with this problem in Latvia,” A. Sauka emphasizes.

In Latvia, a positive trend has been observed in the field of under-reporting of income (profit). Namely, in Latvia, in 2019 the average share of income (%) that entrepreneurs hid from the state decreased by 1.3%, reaching 16.6%. While in Estonia, in 2019 the amount of under-reporting of income reached 10.6% (increase by 0.7%), and in Lithuania, 14.4% (increase by 0.6%). In 2019, the amount of non-reported employees (average % of employees who work without a contract from the total number of employees) increased in all three Baltic countries, reaching 10.9% in Latvia (increase by 1.0%), 8.3% in Lithuania (increase by 2.9%), and 5.7% in Estonia (increase by 0.3%). “This indicator is closely related to the shortage of labour in Latvia and illegal importation of labour from other countries. The issue of local labour shortages, especially the availability of so-called “blue-collar” labourers, will largely lose its relevance in the event of an economic downturn,” A. Sauka emphasizes.

The shadow economy in Latvia is most prevalent in the Riga region, in Zemgale, and in Kurzeme. In terms of sectors, the highest share of the shadow economy still comes from the construction sector.

According to the results of the study, in 2019 the general level of bribery in Latvia reached 8.1% (decrease by 0.2% compared to 2018); in Lithuania, 8.5% (decrease by 1.4%); and in Estonia, 3.9% (decrease by 1.1%).

Involvement or non-involvement in the activities of the shadow economy is influenced by several factors, and from the factors considered in the study, it is mostly related to dissatisfaction with the quality of business legislation and the State Revenue Service, followed by satisfaction with tax policy and state support for entrepreneurs. “Regarding attitude, companies in the Baltic countries are still relatively satisfied with the operation of the State Revenue Service (SRS). In addition, in all three Baltic countries satisfaction with the SRS slightly increased in 2019: on a scale of 1-5, where 5 means very high satisfaction, in Latvia the satisfaction of entrepreneurs with the SRS was assessed at 3.5 (3.39 in 2018); in Lithuania, 3.7 (3.53 in 2018); and in Estonia, 3.8 (3.57 in 2018),” A. Sauka emphasizes.

Satisfaction with the state tax policy has also increased in all three Baltic countries, but especially in Lithuania and Estonia. While in 2018 in Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia entrepreneurs assessed their satisfaction with tax policy at 2.36, 2.85 and 2.41, respectively, in 2019 the assessments were 3.10, 3.10 and 2.60 (on a scale 1 to 5, where 5 means very high satisfaction). Satisfaction with the quality of business legislation has also slightly increased in all three Baltic countries, ranging from 3.01 to 3.35 in 2019. In turn, satisfaction with the state’s support for entrepreneurs in the Baltic countries in 2019 was approximately at the same level as in 2018 - in the range of 2.42-2.85.

The results of the study show that entrepreneurs who consider tax evasion to be a permissible behaviour are more involved in the shadow economy. The study also shows that the higher the perceived probability of getting caught and the higher the penalties for being caught, the lower the involvement in the shadow economy. “These results show possible policy initiatives for reducing the size of the shadow economy, namely by increasing the probability that those entrepreneurs who engage in the shadow economy will be caught and will be adequately punished,” explains A. Sauka. Another important factor in the decision to engage in the shadow economy is the size of the company: smaller and younger companies are more involved in the shadow economy than larger companies.

“The results of the study indicate the need to continue reforms and other policy initiatives to reduce the shadow economy, both in Latvia and in the other two Baltic countries. It is especially important to implement such reforms, including reviewing the approach to limiting the size of the shadow economy, taking into account the economic downturn that is expected in the coming years,” A. Sauka points out.